Author: Lee, J., Ritchotte, J., & Zaghlawan, H.

Publications: Parenting for High Potential

Publisher: NAGC

Year: March 2017

Although Ryan was being considered for gifted and talented services in second grade based on his performance in reading and math, he greatly disliked in-class reading. He was disengaged in class because he was forced to read books that he didn’t find interesting, and he felt he already knew what was being taught. He stopped reading the books his teacher chose for him. He learned quickly that he could do fine on the computerized reading tests without reading those “boring” books.

Several months after Ryan made this choice, his teacher attempted to engage him in a conversation on yet another book he had not read. It surprised her that Ryan could not answer simple questions about the book, but had earned a high mark on his reading test. After a little more questioning, she realized that Ryan had also not read the other books she had chosen for him earlier in the school year. Ryan’s parents received the phone call that every parent dreads. The teacher informed them that Ryan would be placed on a behavior plan for his dishonesty. His parents accepted this consequence, punished Ryan by taking away his video games for a month, and did not attempt to uncover why Ryan chose to behave in such a way.

Like many well-intentioned parents, they did not realize that uncovering why could prevent similar problem behaviors from reoccurring in the future and help place Ryan on a path to engagement in school.

What is Meaningful Engagement?

Research has shown that when children feel engaged with learning, they are more likely to flourish socially and academically1 and less likely to exhibit problem behaviors.2 Researchers have distinguished three different types of engagement: behavioral, emotional, and cognitive.3 Behavioral engagement focuses on participation in academic, social, and out-of-school activities.

Emotional engagement centers on how connected children feel to their teachers, peers, and what they are learning in school. Lastly, cognitive engagement occurs when children are invested in their learning and put forth effort into understanding challenging material. (see below).

| Types of Engagement | Examples |

|---|---|

| Behavioral | "I complete homework on time." "I work hard to do well." |

| Emotional | "I feel happy to be part of my school." "I enjoy the classes I am taking." |

| Cognitive | "I want to learn as much as I can at school." "School is important for future success." |

(Fredricks et al., 2011)

Meaningful engagement encapsulates all three types of engagement. In other words, children who are meaningfully engaged willingly participate in learning activities, feel connected to what they are learning, and embrace the opportunity to be challenged in school.

Why Are All Children Not Meaningfully Engaged at School?

Unfortunately, it’s not always so simple for teachers to support meaningful engagement in school. First, teachers may not recognize whether a particular learning activity is “meaningful” for a child. Knowing if a child is feeling connected to what he is learning or craving more challenge in a classroom of 25 or more students can be diffi cult. This leads to the second issue, time. In an era of high-stakes testing, it may not always be easy for teachers to provide children with opportunities to meaningfully engage in true learning for extended periods of time because schooling takes precedence. Preparing children for material they will be tested on may seem like more of a priority than allowing children to dig deeper into content that interests them. However, there are ways parents can support teachers in meaningfully engaging their children at school.

The Path to Meaningful Engagement

Often, parents ask their children about their school day only to receive answers that are not very telling like “good,” “fine,” “I don’t know,” or “I don’t want to talk about it now.” Second, well-intentioned parents often put “Band-Aids”—a temporary solution— on children’s problem behaviors. A Band-Aid solution to a problem behavior might consist of rewards for modifying the behavior (e.g., I earn an inexpensive toy if I turn in my homework on time for an entire week) or consequences for continuing to engage in the problem behavior. Typically, problem behaviors will continue to resurface if the underlying cause of a child’s problem behavior has not been addressed.

The first step to placing children on the path to meaningful engagement at school happens at home.

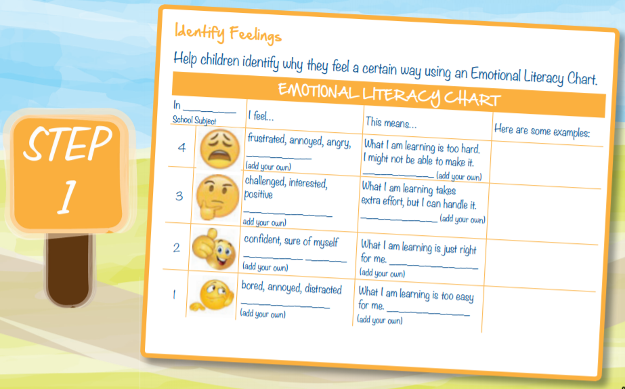

Help Children Identify How They Feel

Helping children identify their feelings is commonly referred to as emotional literacy. Children may not always understand how they are feeling or have the words to explain their feelings.4 Developing children’s emotional vocabulary provides them with appropriate language that is used to articulate both simple and complex feelings. Children with a strong foundation in emotional literacy are able to explain why they engaged in a particular behavior. With that said, it is equally important that children are also able to identify and explain positive feelings (e.g., pride, empathy). Ultimately, children need to learn that expressing feelings with appropriate language is a powerful tool that not only promotes healthy communication, but also helps them get their individual needs met.

One way parents can help their child identify how he feels about schoolwork he is not excited about and why he feels this way is by using an Emotional Literacy Chart (see page 9). Parents can model or act out these different feelings, brainstorm examples of the different feelings, and even find “teachable moments” throughout the day to explain their own feelings. Parents can use the Emotional Literacy Chart during homework time or downtime or whenever the child feels most comfortable reflecting on his day at school.

Using the chart as a tool, children are encouraged by the adults in their lives to use and grow their emotional vocabulary. Once they master a basic emotional vocabulary, their parents can help add complex feelings and advanced vocabulary. It’s important to point out that complex feelings are described using more than one word. For example, “sad” is a basic feeling, while “I don’t feel confident right now” is a more complex phrase that might be associated with sadness. Helping children accurately identify and explain their feelings at home is the first step to meaningfully engaging children at school.

Communicate with the Child’s Teacher(s)

Effective communication between parents and teachers is essential. Ongoing verbal and nonverbal communication between parents and teachers is the cornerstone of a successful partnership. Communicating only when a problem presents itself is reactive and not proactive. When faced with a problem, blaming others— or even ourselves—is very unlikely to lead to positive outcomes. Ongoing communication through occasional phone calls, emails, or a school-home communication notebook can prevent the emergence of future concerns.5 These various means of communication are simple but powerful because they promote the sharing of ideas and feedback about the child’s level of engagement at school and home—and keep both parents and teachers informed about the child’s evolving interests and motivation toward learning.

Parents might start a conversation with their child’s teacher(s) by sharing the child’s Emotional Literacy Chart. In addition, parents should encourage their child to share her feelings with her teacher. The teacher might have a different perspective, so listening is always important. Keeping copies of the Emotional Literacy Chart and Feelings Tracker in the child’s folder, on his desk, or in his school planner will help keep track of communication over a longer period, The chart may be laminated and reused each day.

Offering children a simple way to begin a conversation with their teachers about their engagement lays the foundation for self-advocacy in the future. Gifted children, especially, need to learn at a young age how to express when they have learning needs in a way that is appropriate and comfortable for them. As children get older, it becomes increasingly more diffi cult for parents to advocate on their behalf at school. Modeling effective adult communication between parent and teacher, in addition to giving children an opportunity to express how they are feeling, are proactive strategies that support continued meaningful engagement in school.

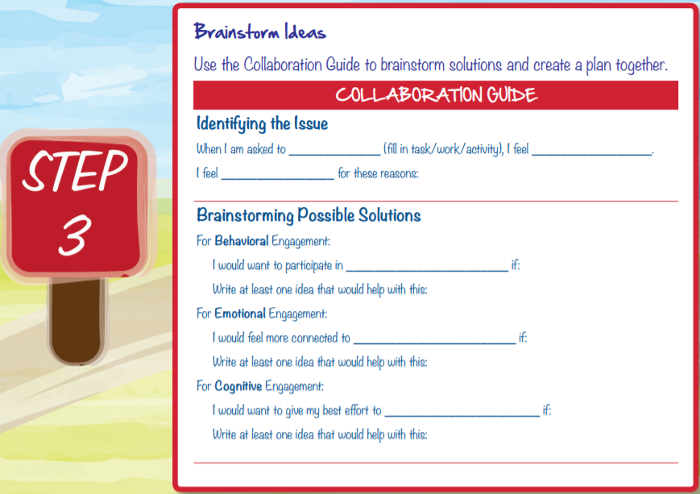

Collaborate on a Plan

Once a child’s feelings toward a particular subject are identified, the next step is to brainstorm practical solutions. Brainstorming solutions should always be a collaborative effort that includes parents, teachers, and, of course, the child!

Shared input results in greater investment and buy in on everyone’s part, especially if all voices are heard and honored during the process. Conversations between a child, teacher, and parents begin by using insights gleaned from the Emotional Literacy Chart to complete a Collaboration Guide. The Collaboration Guide is an organizational tool used to help facilitate a discussion around an issue and to brainstorm solutions that address the components of meaningful engagement. The Collaboration Guide is comprised of sections that align with the components of meaningful engagement:

- Identifying the Issue, where information is taken from the Emotional Literacy Chart and Feelings Tracker previously completed by the child and confirmed during the meeting.

- Brainstorming Possible Solutions, where the team creates a list of possible solutions that might address the issue.

Simply agreeing to try an idea is often not going to lead to hoped-for outcomes. The child needs to reflect on why she wants to try this idea and identify the steps she will take to implement it. If a child is not invested in trying a particular idea, it is destined to fail because he/she will most likely not put forth the effort needed to make it work.

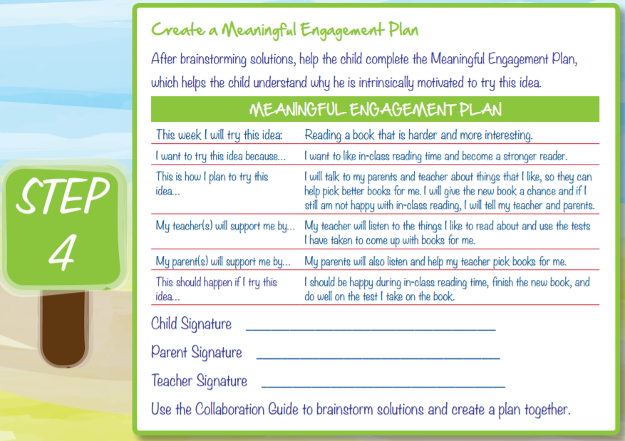

After brainstorming ideas for solutions, the team helps the child complete the Meaningful Engagement Plan. This tool helps the child understand why he is intrinsically motivated to try this idea. Intrinsic motivation or buy in is a critical component.

With the help of his team, the child explains how he will try this idea and how his team members will support him. Getting as specific as possible with details is important.

Finally, the last piece is determining what should happen if everyone does their part. These are the outcomes the child, teacher, and parents can measure. For example, if a child is resistant to reading a book, an Emotional Literacy Chart can help gauge his feelings about the book and a reading assessment will ensure he read the book and understood it.

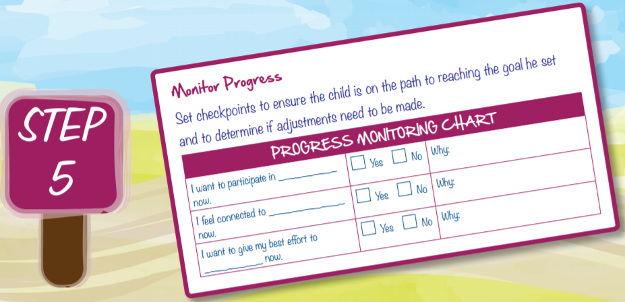

Throughout the implementation process, it is important to set checkpoints to ensure the child is on the path to reaching the goal he set and to determine if adjustments need to be made. The team can use a simple Progress Monitoring Chart. Checkpoints might include mini-goals and deadlines, and could either be done by parents or teachers—but shared with both.

If adjustments are needed to help the child achieve his goal, the Meaningful Engagement Plan can be adapted at this point with everyone’s input. The team can meet again in person, on the phone, or over email. Typically, if the child does not make a goal (as recorded on the Progress Monitoring Chart), then the Emotional Literacy Chart, Collaboration Guide, and Meaningful Engagement Plan tools may need to be reexamined.

Concluding Thoughts

When a child stops engaging in learning, parents and teachers need to feel empowered to change the path the child is on. Band-Aid solutions lead to frustration. A shared partnership between parents, teachers, and the child, on the other hand, leads to empowerment for everyone involved. Without a doubt, it takes a village to help a child maximize his or her full learning potential. High-potential children should never be considered the exception to this rule. They, too, require the support of caring adults in their lives and opportunities to feel meaningfully engaged in learning.

Authors’ Note

Jennifer Ritchotte, Ph.D., is an assistant professor of special education with an emphasis in gifted and talented education at the University of Northern Colorado. Prior to this position, she was a teacher of gifted and talented students at the secondary level. Through publications, conference presentations (state, national, and international), and workshops, she advocates for the needs of gifted students, especially students at risk for adverse educational outcomes.

Hasan Zaghlawan, Ph.D., is an assistant professor and coordinator of the bachelor program in Early Childhood in the School of Special Education at the University of Northern Colorado. His area of research focuses on promoting social and communicative skills for young children with disabilities, developing parent and teacher-implemented interventions to increase children’s engagement in naturalistic environments, and supporting families in preventing and managing challenging behaviors.

Chin-Wen “Jean” Lee, M.Ed., is a doctoral student in the School of Special Education at the University of Northern Colorado. Her research emphasis is on twice-exceptionality. She is interested in teacher preparation, professional development, and program evaluation. During her free time, she likes cooking, baking, hiking, and visiting small towns in Colorado.

Endnotes

- Bevill, A. R., Gast, D. L., Maguire, A. M., & Vail, C. O. (2001). Increasing engagement of preschoolers with disabilities through correspondence training and picture cues. Journal of Early Intervention, 24(2), 129–145.

- Dunlap, G., Strain, P. S., Fox, L., Carta, J. J., Conroy, M., Smith, B. J., … & Sailor, W. (2006). Prevention and intervention with young children’s challenging behavior: Perspectives regarding current knowledge. Behavioral Disorders, 32, 29–45.

- Fredricks, J., McColskey, W., Meli, J., Mordica, J., Montrosse, B., & Mooney, K. (2011). Measuring student engagement in upper elementary through high school: a description of 21 instruments. (Issues & Answers Report, REL 2011–No. 098). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Southeast. http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs

- Fox, L., Hemmeter, M. L., Snyder, P., Binder, D. P., & Clarke, S. (2011). Coaching early childhood special educators to implement a comprehensive model for promoting young children’s social competence. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 31, 178‒192.

- Davern, L. (2004). School-to-home notebooks: What parents have to say. Teaching Exceptional Children, 36, 22‒27.

Permission Statement

Comments