Deeper Dive

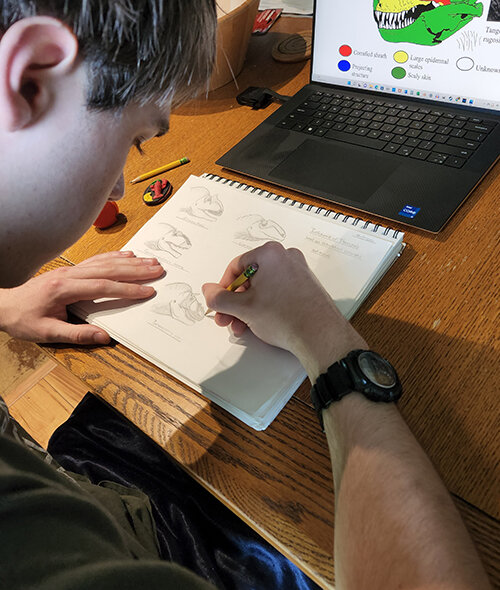

In my research project, I examined bone textures from the skulls of several extinct theropod (meat-eating dinosaur) species (known as allosauroids) to reconstruct the anatomy of their facial skin. This superfamily includes the famed dinosaur Allosaurus. I chose them for my research because their facial skin was completely unknown before. I was originally prompted to do this when I was trying to digitally sculpt an accurate 3D model of the giant allosauroid Giganotosaurus, and I realized that I had no idea what the animal’s face would actually have looked like in life. After a little Internet research, I discovered how other scientists had previously established the relationship between specialized skin tissues in modern animals and the distinctive trace marks left by that type of skin on their skulls, and how these relationships had been used before to reconstruct the facial skin of a few other dinosaur species. For example, a keratin sheath, such as a bird beak, will leave a dense network of elongated grooves on the underlying bone surface. I then applied this method to Giganotosaurus and several of its allosauroid kin by examining high-resolution photographs of their skull bones. After reconstructing their facial skin, I was able to make comparisons with the skin tissues of living animals to infer potential aspects of their appearance, behavior, ecology, and evolution. One major discovery was that some allosauroids, and the more distantly-related tyrannosaurs, independently evolved toughened, armor-like sheets of keratin on large areas of their faces, which were previously thought to only be found in one other, unrelated theropod group known as abelisaurids. The second major part of my research then attempted to investigate what environmental factors were causing these three different theropod groups to develop such similar adaptations. I gathered data on the ancient ecosystems of armor-faced theropods, such as the past climate conditions and local fauna, in order to test three hypotheses that stated facial armor had developed in response to: (1) competition from other predators, (2) an abundance of hazardous prey items, or (3) aggressive competition between individuals of the same species over limited resources in dry climates.

The biggest challenge that I faced during my project was limitations in data availability. The pandemic, of course, prohibited me from examining the fossil specimens in person, which would have improved the confidence level of my results. But for the most part, the pandemic did not stop my research, and I never had to leave my house for purposes directly related to the project. I was able to apply statistical methods that I learned in AP Statistics and AP Biology to test my hypotheses for the evolution of theropod facial armor, but another problem was that only about forty species of theropods showing evidence of facial armor had ever been found, meaning the sample size was too small for me to draw definite conclusions from the statistical tests. I received some statistical advice from my AP Stats teacher, Jill Ninteau, and my AP Bio teacher, Dan Guertin, as well as from Alfred Venne of the Beneski Museum of Natural History at Amherst College and his colleague, Matthew Inabinett of East Tennessee State University. Of course, my project would not have been possible if I had not reached out to and received the generous help of several paleontologists from around the world, who sent me high-resolution photographs of theropod skull bones per my request and permitted me to use some of them in my figures. They include: Dr. Juan Canale of the Ernesto Bachman Municipal Museum, Villa El Chocón, Argentina, Dr. Rodolfo Coria of the Carmen Funes Municipal Museum, Plaza Huincul, Argentina; Dr. Elena Cuesta Fidalgo of the Palaeontological Museum of Munich, Germany; Dr. Paul Sereno and Research Manager Lauren Conroy of the University of Chicago, Illinois, United States; Dr. Hilary Ketchum of the Oxford Museum of Natural History, England; Collections Specialist David Bohaska of the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, United States; Dr. John Scannella of the Museum of the Rockies, Bozeman, Montana, United States; and Dr. Scott Hartman of the University of Wisconsin, Madison, United States.

My project is important because it has revealed the soft-tissue anatomy and external appearance of several long-extinct species for the very first time. This is not only important for our understanding of their anatomy, but it also can tell us information on their behavior and ecology that would be very difficult to infer otherwise. For example, my finding of evidence for specialized skin tissues known as cornified pads on the skulls of some theropods suggests that these animals may have engaged in headbutting, since these tissues are exclusively found in modern headbutting animals like muskoxen, and this helps us better understand the evolutionary history of animal social behavior on a larger scale. My rigorous reconstruction of theropod facial tissues also allows artists to make science-based depictions of these magnificent animals, which are vital for inspiring a profound respect for nature in children and for bringing more people into the natural sciences. Additionally, my investigation into the origins of theropod facial armor may help us understand the way that environmental factors can create selective pressures that shape animal anatomy over time, and this knowledge may one day serve us in the global struggle for animal conservation.