Resource Library

Your gateway to resources for and about gifted students.

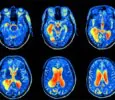

Neuroscience of Giftedness: Larger Regional Brain Volume

by Sharon Duncan, Corin Goodwin, Joanna Haase, Ph.D, MFT, and…

Neuroscience of Giftedness: Physiology of the Brain

by Sharon Duncan, Corin Goodwin, Joanna Haase, Ph.D, MFT, and…

Tips for Students: How to Strengthen Your Inner Ally

The following article expands on highlights and insights from one…

Tips for Parents: Understanding Your Family Ecosystem When You’re Raising PG/2e Kids

The following article expands on highlights and insights from one…

Free Resources and Guides

Families can find gifted resources by browsing popular topics and issues in the gifted community. We also have extensive guides written by the Davidson Institute professionals have been designed to assist families with gifted students.

Support for Educators

Join the online community of professionals committed to meeting the unique needs of highly gifted students.

Davidson Institute Spotify Playlists

Now you can take Davidson with you! We’ve curated topic-specific playlists of the podcast episodes our Family Services Team has been listening to and recommending to families. Now, they are all in one convenient spot, so just follow us on Spotify, and listen along on your schedule!