This paper presents the results of three 2-year longitudinal interventions of the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) homework program in elementary mathematics, middle school language arts, and middle school science. The findings suggest that the benefits of TIPS intervention in terms of emotion and achievement outweigh its associated costs.

Author: Van Voorhis, F. L.

Publication: Journal of Advanced Academics

Publisher: Prufrock Press, Inc.

Volume: Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 220-249

Year: Winter 2011

Homework represents one research-based instructional strategy linked to student achievement. However, challenges abound with its current practice. This paper presents the results of three 2-year longitudinal interventions of the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) homework program in elementary mathematics, middle school language arts, and middle school science. Each weekly standards-related TIPS assignment included specific instructions for students to involve a family partner in a discussion, interview, experiment, or other interaction. Depending on subject and grade level, TIPS students returned between 72% and 91% of TIPS activities, and families signed between 55% and 83% of TIPS assignments. TIPS students and families responded significantly more positively than controls to questions about their emotions and attitudes about the homework experience, and TIPS families and students reported higher levels of family involvement in the TIPS subject. No differences emerged in the amount of time students spent on subject homework across the homework groups, but students using TIPS for 2 years earned significantly higher standardized test scores than did controls. The findings suggest that the benefits of TIPS intervention in terms of emotion and achievement outweigh its associated costs.

What factors affect student academic achievement? Research indicates that in addition to classroom instruction and students’ responses to class lessons, homework is one important factor that increases achievement (Marzano, 2003; Patall, Cooper, & Robinson, 2008). According to Cooper, homework involves tasks assigned to students by schoolteachers that are meant to be carried out during noninstructional time (Bembenutty, 2011). Although results vary, meta-analytic studies of homework effects on student achievement report percentile gains for students between 8% and 31% (Marzano & Pickering, 2007). If homework serves a clear benefit for students, it is puzzling why there are persistent discussions and contention about its practice (Bennett & Kalish, 2006; Kohn, 2006; Kralovec & Buell, 2000). Homework requires students, teachers, and parents to invest time and effort on assignments. Their views about homework vary. On a positive note, 90% of teachers, students, and parents believe homework will help students reach important goals. Yet, 26% of students, 24% of teachers, and 40% of parents report that some homework is just busywork, and 29% of parents report homework is a “major source of stress” (Markow, Kim, & Liebman, 2007, p. 15).

It is critical, then, to improve current practice and for educators and researchers to examine the emotional and cognitive costs and benefits of homework for students, families, and teachers (Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001; Van Voorhis, 2004, 2009, in press; Van Voorhis & Epstein, 2002). The purpose of this paper is to describe the results of one homework intervention designed to ease some homework tensions between students and families. The Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) interactive homework process draws on the theory of overlapping spheres of influence, which stipulates that students do better in school when parents, educators, and others in the community work together to guide and support student learning and development. In this model, three contexts—home, school, and community—have unique (nonoverlapping) and combined (overlapping) influences on children’s learning and development through the interactions of parents, educators, community partners, and students. Each context moves closer or farther from the others as a result of external forces and practices that encourage or discourage the internal interactions of the partners in children’s education (Epstein, 2011; Sanders, Sheldon, & Epstein, 2005).

Costs and Benefits of Family Involvement in Homework

Three aspects of homework that entail costs and or produce benefits for home and school contexts are time, homework design, and family involvement. A common complaint about homework, and one of the most studied factors, is time on homework. Data on the time students spend on homework vary based on who reports it (Bembenutty, 2009; Hoover-Dempsey et al., 2001; Kitsantas & Zimmerman, 2009; Warton, 2001; Xu, 2009), as do recommendations about sensible requirements for time on homework. Specifically, parents of elementary students have a fair sense of their children’s homework responsibilities, but in the secondary grades, parents often underestimate the frequency of homework assignments and overestimate the time their children spend (Markow et al., 2007).

Some teachers tend to underestimate how often families are involved. In one study of middle school students, parents helped their children with homework, on average, between one and three times per week and checked homework four times per week (Eccles & Harold, 1996). Students reported working with their parents on schoolwork between one and three times weekly. However, students reported that teachers asked them to request parental assistance only one to two times per month on tasks such as checking homework, studying for tests, or working on projects.

These discrepancies are just one example of homework communication problems among all parties involved. Overall, like many education issues, a percentage of students at all grade levels (5% of 9-year-olds, 8% of 13-year-olds, and 11% of 17-year-olds) spend a lot of time on homework (> 2 hours per night); others complete none at all or fail to complete assigned work (24% to 39%); and many are right in the middle, completing less than 1 hour (28% to 60%) or between 1 and 2 hours per night (13% to 22%; Perie & Moran, 2005). Some studies conducted on the relationship of time on homework and achievement find that the age of the student moderates the relationship. Specifically, the homework and achievement relationship is stronger and positive for secondary students and negative or null for elementary students (Cooper, 1989; Cooper, Robinson, & Patall, 2006). The studies have resulted in different time expectations for younger and older students. Many schools have adopted the 10-minute rule as a general guide for developmentally appropriate time on homework (Henderson, 1996). For example, students in the elementary and middle grades should be assigned roughly 10 minutes multiplied by the grade level (i.e., 30 minutes for a third-grade student), while high school student assignment time varies by subject. The time differences also raise some questions about different purposes and content of homework across the grades.

Issues of purpose and content relate to the next topic, homework design. There are instructional (practice, preparation, participation, and personal development) and noninstructional or nonacademic (Corno & Xu, 2004) purposes of homework (parent-child relations, parent-teacher communications, policy; Epstein & Van Voorhis, 2001). Not surprisingly, more than 70% of homework assignments by teachers at all levels of schooling are designed for the purpose of students finishing classwork or practicing skills (Polloway, Epstein, Bursuck, Madhavi, & Cumblad, 1994). Homework in the early grades should encourage positive attitudes and character traits, allow appropriate parent involvement, and reinforce simple skills introduced in class (Cooper, 2007). For secondary grades, homework should work toward improving standardized test scores and grades. Teachers report that the homework process needs to improve, and that they would like time to ensure that assignments are relevant to the course and topic of study; build in time for feedback on assignments daily; and establish effective policies at the curriculum, grade, and school levels (Markow et al., 2007, p. 136).

Homework design also needs to develop the third topic— family involvement in the homework process. Families report that homework costs them time and energy when teachers fail to explain the assignment to students in class, assignments do not relate to classwork, or when students are unsure about how to complete it. Parents report that they sometimes provide poor or inappropriate help, often feel unprepared to help with certain subjects (Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Burow, 1995; Markow et al., 2007), and sometimes spend time trying to motivate their children to complete their homework by making the assignment more interesting. The quality of the family-student interactions not only affect students’ completion of homework and achievement, but also children’s emotional and social functioning (Pomerantz, Moorman, & Litwack, 2007).

Kenney-Benson and Pomerantz (2005) simulated a lab homework experience and found that elementary students with mothers who were involved in an autonomy-supportive manner were less likely to experience depressive symptoms than children with controlling mothers. Similarly, junior high students who perceived their parents as supportive of their academic endeavors exhibited less acting-out behavior (Grolnick & Slowiaczek, 1994). In fact, parents of both elementary and middle grade students reported that they would help their children more if the teacher guided them in how they could help at home (Dauber & Epstein, 1993; Kay, Fitzgerald, Paradee, & Mellencamp, 1994).

Aim of the Study

This present discussion of homework suggests that issues of time, design, and family involvement can influence students’ homework experiences and the results of their efforts. This study presents the results of a homework intervention that helps teachers consider issues of time, design, and family involvement in their assignments for students. Three 2-year intervention studies of the Teachers Involve Parents in Schoolwork (TIPS) Interactive Homework process were conducted—the first longitudinal studies of the TIPS process. This study summarizes the findings from the three studies combined, looking across the elementary and middle grades, three courses, and diverse community contexts to address three main research questions:

- Students’ work: What percent of TIPS activities were completed and how well? How much time was invested by students?

- Student and family emotional investments: How did emotions and attitudes about homework compare for TIPS and control groups?

- Student outcomes: How did student achievement(s) compare for TIPS and control groups over 2 years?

Overall, given the attention to student and family roles in homework and a regular schedule of weekly, standards-based interactive homework, it was hypothesized that the students and families in the TIPS groups would experience more positive emotional homework interactions and higher achievement than the students and families in the control group.

Method

Participants

The sample included students in an elementary mathematics intervention in third and fourth grades (Van Voorhis, 2009, in press), a middle school language arts intervention in sixth and seventh grades (Van Voorhis, 2009), and a middle school science intervention in seventh and eighth grades (Van Voorhis, 2008). This combined study sample included only students who participated in 2 years of the study who were control students (no use of TIPS either year), TIPS 1-year students (TIPS in either Year 1 or 2), and TIPS 2-year students (TIPS use both years). All three studies—the elementary math (2004–2006), middle school language arts (2005–2007), and middle school science study (2006–2008)—took place in schools in urban southeastern school districts. There were 4 similar elementary schools (grades K–5); and 5 middle schools (grades 6–8). At each school, teachers were randomly assigned to implement either the TIPS interactive homework assignments weekly along with other homework or to serve as control teachers and assign only regular, noninteractive homework assignments. Thus, teachers were randomly assigned to the intervention and control conditions. Although students were not randomly assigned to classrooms, every effort was made to select similar, average classrooms of students.

The full sample included 575 students in 9 schools. Overall, 30% of the sample represented control students, 35% were TIPS 1-year students, and 35% were TIPS 2-year students. Elementary math students comprised 16% of the sample, 49% were middle school language arts students, and 35% were middle school science students. Fifty-seven percent of students received free or reduced-price meals, and 51% of students were male. The majority of students (52%) were African American, 42% were White, and 6% were Hispanic. The average previous standardized test score of students was 51.8%. Eighty-one percent of the full sample of students represented average-achieving students, 11% represented gifted students, and the remaining 8% of students were below average.

Each year, teachers administered student and family surveys on attitudes about homework in general and TIPS homework in specific subjects. Eighty-nine percent of students in Years 1 and 2 returned surveys, and 80% of families in Year 1 and 65% of families in Year 2 completed them. Overall, 36 teachers served as TIPS (19) or control (17) teachers over the course of the study, 44% of whom taught elementary math, 36% taught middle school language arts, and 20% taught middle school science. These teachers had taught an average of 13 years and had worked at their respective schools an average of 6 years.

TIPS Intervention

For one week during the summer prior to the start of each TIPS year, the author provided professional development to the TIPS teachers in each subject area to enable them to understand the research on homework, designs for interactive homework, and to adapt and/or develop TIPS activities based on their own district’s curriculum objectives. All TIPS activities, regardless of subject, include four common components: letter to family partner, various kinds of student-led interactions, home-to-school communication, and parent/guardian signature (Epstein et al., 2009). In each activity, students and families are instructed where an interaction (i.e., discussion, interview, survey, experiment) is to occur and the roles the student and family partner play in the interaction. For example, in a third-grade math activity, students practice counting money and writing it in two ways. The student completes several practice problems independently and shows his work on two of them to his family partner. Then, the student and family partner each put a few coins in their hands. The student counts both his coins as well as the family partner’s and records the answers. For a middle school science activity, the student examines a chart of physical, social, emotional, and intellectual changes and records the changes she has observed in life. The student and family partner then discuss questions like “Which changes are you happy about, and which changes are you least happy about?”

Two-way communications are encouraged in home-to-school communication that invites the family partner to share comments and observations with teachers about whether the child understood the homework, whether he enjoyed the activity, and whether the parent gained information about the student’s classwork.

Teachers designed each interactive TIPS activity for two sides of one page, linked them to the curriculum and to class lessons, and described them as the student’s responsibility to complete despite the request for family involvement in certain sections. Teachers also assigned point values to questions in all TIPS assignments to provide consistency in grading across teachers.

Procedure

TIPS condition. During the summer work time, the TIPS teachers wrote a letter to the families of students in their classes. This letter included information on the weekly use of TIPS, the grading schedule, and the expectation for a family partner to participate with the student. Teachers of TIPS students in the math and language arts studies assigned one assignment weekly for a total of 30 TIPS activities each year, in addition to their other homework. Students in the control group completed homework as usual. More specifically, for the elementary math and language arts studies, teachers in the control group used their normal homework practices and homework. In discussion with these teachers prior to the school year, the author learned that they rarely asked families to be involved in homework. For both subjects, control and TIPS teachers generally assigned worksheets and problem sets to practice math facts and concepts introduced in class or worksheets and writing assignments for language arts. Both TIPS teachers and teachers in the control group assigned homework almost every week night, with TIPS teachers assigning TIPS once a week and the control group teachers assigning an independent activity. Science homework occurred less frequently, generally once or twice per week. Like the other studies, control science teachers assigned an independent assignment while TIPS teachers assigned the TIPS activities, at most once per week. In this study, TIPS students completed 24 activities in Year 1 and 17 in Year 2.

Teachers graded TIPS and all other homework and provided these data to the author every 9 weeks. At the end of each school year, TIPS students, families, and teachers completed an end-ofyear survey on homework in the TIPS subject.

Control condition. The author met with the teachers in the control group for 1 day in the summer prior to the school year of TIPS implementation for each year of each study. The author reviewed the basic goals of the study and explained to these teachers the types of data she would be collecting every 9 weeks during the school year. Students, families, and teachers in the control group also completed an end-of-year survey on TIPS subject homework.

Independent Variables

The independent variables that showed significant differences across homework groups were statistically controlled in regression analyses. These included gender, free or reduced lunch status, class ability grouping (below average, average, above average), race/ethnicity (Black, White, or Hispanic), study subject (elementary math, middle school language arts, or middle school science), years of teacher experience in Year 1 or 2, and previous standardized test scores (e.g., for third- and fourth-grade students, this would be the second-grade test score). Homework condition (control or TIPS for 1- or 2-years) represented the experimental variable of interest.

Dependent Variables

The dependent variables included time, attitudinal, family involvement, and achievement outcomes. The child and parent time and attitudinal variables included the following:

- time child spent on all and subject-specific homework on an average night (0 = 0 minutes, 1 = about 15–20 minutes, 2 = about 30–40 minutes, 3 = about 1 hour, 4 = more than 1 hour, and 5 = more than 2 hours for students and families);

- levels of family involvement in language arts, math, and science homework (students: 0 = never, 1 = a few times, or 2 = a lot; parents: 0 = never, 1 = rarely, 2 = sometimes, 3 = frequently, or 4 = always);

- student ratings of mother’s/father’s and own feelings while working on homework (0 = don’t work with mom/ dad, 1 = unhappy, 2 = ok, or 3 = happy; scale consists of two items: α = .88 for mother, .90 for father);

- family ratings of own and child’s feelings while doing homework (scale consists of two items: α = .73; 1 = very frustrated, 2 = frustrated, 3 = a little frustrated, 4 = ok, 5 = a little happy, 6 = happy, or 7 = very happy);

- student attitudes about homework interaction (scale consists of four items: α = .76; 0 = disagree, 1 = agree a little, or 2 = agree a lot); and

- family attitudes about homework interaction (scale consists of four items: α = .68; 1 = disagree, 2 = agree a little, or 3 = agree a lot).

Achievement variables included homework completion measures, report card grades, and standardized test scores in the TIPS subject. These standardized test scores represented student performance on the mathematics, reading/writing, or science sections of the district’s assessment program, including criterion-referenced items directly aligned with the subject-specific content standards and state performance indicators.

Data Analysis

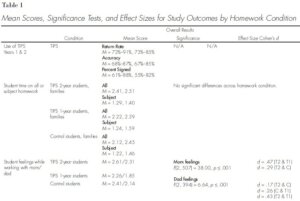

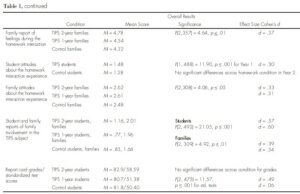

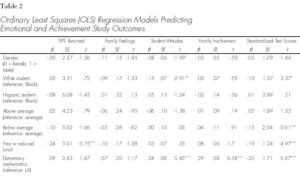

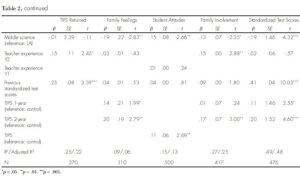

The researcher conducted descriptive results and inferential statistics to understand the impact of the TIPS intervention on several key outcomes. Table 1 includes descriptive results, ANOVA F statistics, and effect sizes for the homework groups, mainly in Year 2. In every instance reported in Table 1 where a Year 2 result was significant and favoring the TIPS group(s), similar significant results emerged in Year 1. For ease of presentation, only Year 2 results are presented, with the exception of student reports of homework attitudes. Table 2 provides the results of full regression models, taking into account the interplay of various background variables on the following dependent variables: (a) percent of TIPS returned, (b) family reports of homework feelings, (c) student reports of homework attitudes, (d) student reports of family involvement in homework, and (e) standardized test scores.

Results

Use of TIPS

Across studies, students completed most assignments with 91% of assignments completed by math students, 81% completed by language arts students, and 72% completed by science students in Year 1 (see Table 1). Worthy of note is that family partners signed 83% of math assignments, 61% of language arts, and 64% of science activities. Put another way, most families were involved in some way with their children in math on average 25 times over the course of Year 1, 18 times in language arts, and 15 times in science. Even in Year 2 when percentages of signed assignments generally dropped, Year 2 families generally interacted with their students in some way in math on average 25 times, in language arts 17 times, and in science about 13 times.

Table 2 displays the relationship of background variables on percent of TIPS assignments returned in Year 2. For all regression models, the author entered variables step-wise beginning with gender through free-reduced lunch for Model 1, TIPS study subject variables added for Model 2, teacher experience with all previous variables represented Model 3, previous standard score for Model 4, and the homework condition with all previous variables in the full model. This Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression model, accounting for 22% of the variance in returned TIPS, indicates that students receiving free and reduced-price meals tended to turn in significantly fewer TIPS than those not receiving meals. In addition, students with teachers in Year 2 having more teaching experience tended to return more TIPS than students with teachers having less experience. Finally, and not surprisingly, students with higher previous standardized test scores tended to turn in more TIPS assignments.

Time on Homework

Student and family reports on the time students spent on subject-specific homework did not differ for the TIPS and control conditions. Students using TIPS and those who did not reported an average of between 15–20 minutes and 30–40 minutes of nightly homework in the TIPS subject. Although family reports were slightly higher, they were within the same time ranges. Specifically, 68% of students in both TIPS and control groups reported 15–20 minutes in the specific TIPS subject, while 16% to 20% reported 30–40 minutes per night.

Significant differences emerged, however, in student and family reports of time spent on homework across the subjects (elementary math, middle school language arts, and middle school science). As expected, elementary math students reported spending less time on all homework (M = 1.82) than did middle school language arts students (M = 2.33) or middle school science students (M = 2.43; F(2, 445) = 7.62, p ≤ .001). Similar significant results occurred for student and family reports of time on subject homework only.

Feelings About Homework Interactions

Student reports. Students evaluated their own and their mother’s feelings while working together on subject-specific homework (two-item scale, α = .88). Significant differences emerged across homework condition for both years of the study, with TIPS 2-year students (M = 2.61) reporting more positive feelings than control students (M = 2.41), resulting in an average experience between ok and happy. In Year 2, for example, 66% of TIPS 2-year students indicated a happy homework experience while only 51% of control students did so. Although the means were lower, between unhappy and happy, similar significant results favoring the TIPS 2-year families emerged for student reports of their own and their father’s feelings.

Family reports. Families evaluated their own and their child’s feelings while working on homework together (two-item scale, α = .73). Like the students, TIPS families rated their interactions significantly more happy than control families both years. Specifically, TIPS 2-year families rated their feelings significantly higher (M = 4.78, ok) than control families (M = 4.32, ok). In fact, while 51% of TIPS families reported a happy experience, only 32% of control families did so. Although TIPS 1-year family reports were higher than control families, the differences were not significant.

Table 2 displays the regression analyses for family feelings about the homework interaction in Year 2. Although this full model explains only 6% of the variation in feelings, it does indicate that only three variables were significant predictors of family homework feelings. Families of middle school science students reported significantly less positive homework feelings than language arts students. In addition, families in both TIPS groups reported significantly more happy feelings than families in the control group.

Homework Attitudes

Student reports. Students answered four questions each year about the quality of the homework interaction experience (four-item scale, α = .76). Specifically, they gauged their level of agreement or disagreement with the following statements: (a) My family partner liked working with me on TIPS/subject specific homework; (b) TIPS/subject homework helped my family partner see what I am learning in that subject; (c) My family partner likes to hear what I am learning in school; and (d) I am able to talk about the subject with my family partner. Significant differences emerged in Year 1 only. TIPS students more often agreed with the above statements (M = 1.48) than did control students (M = 1.28). Although 29% of TIPS students agreed a lot with the statements, only 11% of control students did.

Table 2 presents the regression model for student attitudes about homework in Year 1. Background variables explained significant variation in attitudes beginning with male students reporting less positive attitudes than female students. White students tended to report less happy attitudes than did Black students. Additionally, elementary math students reported better attitudes than did middle school language arts students, and middle school science students reported worse attitudes than middle school language arts students. Finally, students in the TIPS condition reported happier attitudes than did control students, with the full model accounting for 13% of the variation in student attitudes.

Each year, students reported whether or not homework was important to them. There were no significant differences across homework conditions on this measure. Students rated homework quite positively, with 81% of control, 87% of TIPS 1-year, and 87% of TIPS 2-year students reporting that homework was important to them in Year 2.

Family reports. Families responded to four survey questions similar to what the students answered about their homework attitudes and working together (four-item scale, α = .68). Again, TIPS families reported significantly more favorably to these questions than control families both years. Whereas 20% of control families “agreed a lot” to these statements, 34% of both TIPS 1- and 2-year families “agreed a lot.”

Levels of Family Involvement in the TIPS Subject Homework

Students and families reported their impressions of the level of family involvement in the TIPS subject homework for both years, and all reports differed significantly by homework condition. For example, TIPS 2-year students reported significantly higher levels of family involvement in subject homework than both control and TIPS 1-year students (see Table 1). Specifically, 88% of TIPS 2-year students reported being involved “a few times” or “a lot,” while 65% of TIPS 1-year and 78% of control students did so.

Families also gave their impressions of family involvement in homework, with significant differences in favor of both TIPS groups over the control group. Although 50% of families in the control group reported being “never” or “rarely involved” in homework, only 30% of TIPS families reported so.

Table 2 displays the results of OLS regression analyses predicting variation in student reports of family involvement in Year 2 TIPS subject homework. The full model predicts 25% of family involvement variation. Elementary math students reported significantly higher levels of family involvement in the TIPS subject than did middle school language arts students. In addition, middle school science students reported less family involvement than did middle school language arts students. Students of teachers with more teaching experience reported higher levels of family involvement than those students of teachers with lesser experience. Finally, only TIPS students using the intervention for 2 years reported significantly higher levels of family involvement than did students in the control group.

Student Achievement

The author ran OLS regression models to explore the effects of TIPS versus control homework conditions on standardized test scores. The complete model accounted for 48% of the variance in Year 2 standardized scores (see Table 2).

The full regression analyses show some effects of student background variables. Specifically, White students earned significantly higher scores than Black students; below-average students and those receiving free or reduced-price meals earned significantly lower scores; elementary math and middle school science students earned significantly lower scores than middle school language arts students; and students with higher previous scores (β =.41, p < .001) earned significantly higher Year 2 scores.

Over and above all of these variables, students in the TIPS 1-year (β = .11, p < .01) and TIPS 2-year (β = .20, p < .001) groups earned significantly higher scores than control students. The effect size represented by Cohen’s d was .49 for TIPS 2-year and control, and minimal for the TIPS 1-year and control groups at .06. In similar analyses, homework condition did not significantly affect report card grades.

Effect Sizes

Overall, of the 15 reported effect sizes (Cohen’s d) related to feelings, attitudes, family involvement, and achievement results in Table 1, 11 favored the TIPS 2-year group either over the control (.17 to .57) or TIPS 1-year groups (.43 to .60), two favored the TIPS 1-year group over control (.31 to .34), one effect was minimal (.06), and only one effect size favored the control group over TIPS (.26). These effect sizes were sizable, ranging from d = .17 to d = .60. Comparing the achievement effect size (d = .49) of this study to other reported studies of homework and achievement (.21 < d < .88; Marzano & Pickering, 2007), one may see that the results of this weekly homework intervention fall appropriately within established effect size ranges of meta-analytic studies.

Discussion

This study examined whether the costs associated with the TIPS interventions are outweighed by the benefits to students, families, and teachers. Time and money represent the main identifiable costs of implementing the TIPS process. Time is required of teachers for 1 week in the summer for professional development and TIPS materials development and in the school year (i.e., time to orient students and families to TIPS, explain each TIPS assignment in class, grade it, and follow up with students about assignments). Students and families also contribute time to work on assignments together over the course of the school year. In addition, schools must acquire funds to pay the teachers for their professional development time in the summer and for duplicating assignments for distribution to students.

The author examined the costs and benefits of the TIPS intervention over 2 years with data collected by the TIPS and control teachers, students, and families on homework assignments, and measures of emotional, attitudinal, and achievement results. Comparisons across groups and the regression analyses for several important emotional and cognitive outcomes produced several lessons learned that inform research and educators about potential improvements to the homework process in terms of time, design, and family involvement.

Lesson 1

TIPS helped students and families engage positively over homework. Prior studies indicate that many students and families view homework as a source of stress and tension in the family system. In looking at both the feelings and attitudes reported by students and families each year, the TIPS group reported significantly more happy homework experiences and fewer frustrating experiences than did the control group. As noted by one parent whose student received TIPS Language Arts assignments, “TIPS [LA] was one thing that we enjoyed working on together!”

In addition, when students and families reported their attitudes about the homework experience, TIPS students and families reported more positive interactions than did control students and families. Although developmental differences were apparent on some measures, the majority of both elementary and middle school students and families rated TIPS as a good idea. Families reported that they would be willing to use the program the following year, as in this parent’s comment:

- We enjoyed the worksheets [TIPS Math]. They were easy to understand, but you were still learning new things. There were interesting games and ideas. I think you should continue them because I am not a math person and I enjoyed them.

With respect to reports of levels of family involvement in homework, significant differences emerged for the TIPS group over control groups, particularly for students and parents who were assigned TIPS for 2 years.

Lesson 2

Sustained use of the TIPS design related to gains in student standardized achievement. The regression analyses demonstrated significant and positive effects for the TIPS groups on standardized test scores. This is an age where numbers talk and schools are rated on their abilities to help students attain high levels of proficiency on standardized test scores. In this study, it was interesting that the TIPS process affected standardized test scores but not report card grades. The fact is that TIPS assignments related directly to the district’s curriculum standards addressed on the high-stakes standardized test scores. In the summer professional development time, teachers thought about homework as a vehicle to strengthen their teaching practice and increase students’ discussions with their family on content standards. Therefore, students in the TIPS groups had weekly opportunities to talk with family partners about critical concepts and skills.

Lesson 3

Better homework practice does not necessitate more student time, but it does require improved homework design and professional development time for teachers. Students in TIPS and control conditions spent about the same amount of time on homework in elementary math, middle school language arts, and middle school science. This suggests that the differences in students’ and families’ attitudes and achievement test scores related to issues other than time. TIPS assignments did not magically appear. Teachers had to devote time to select or develop interactive homework assignments for the school year. In discussion with TIPS and control teachers, they rarely had uninterrupted time to focus solely on designing and developing homework. In the professional development process, experienced teachers mentored and assisted newer teachers. The teachers not only began to share homework tips, but also exchanged classroom teaching techniques and strategies. As noted by one TIPS teacher, “TIPS were relevant and useful in teaching students the state’s seventhgrade curriculum.”

Limitations of the Study

Despite this research’s strengths, future longitudinal homework interventions may be expanded by addressing its limitations. Three specific areas of improvement relate to additional baseline survey measures, more variables to assess teacher implementation, and nested analyses of outcome data.

The current study required a strong partnership between the associated schools and university. As with any study, the researcher had a longer list of variables and measures to collect than what ultimately resulted. Teachers participated in summer professional development time, collected specific homework data every 9 weeks above and beyond what they normally recorded, and organized the student and family survey collection at the end of the school year. These activities represented additional work beyond normal teaching, and therefore, the researcher did not also administer a baseline survey of students and families. Future investigations that include such data would permit more detailed understanding of the changes in emotions and tone of student and family homework interactions over time as a result of the intervention. Additionally, by looking at the data separately in student and family groups as well as in student and family dyads, we may better understand the dynamics of the interactions and how they may vary by gender, grade level, and previous achievement.

Along those lines, more qualitative and quantitative studies of teacher homework implementation may illuminate some of the differences that may have emerged across homework treatment groups. Teachers did complete a brief survey of their actions to introduce, grade, and follow up TIPS and or other homework activities. No significant differences emerged across the groups with the exception of the TIPS teachers explaining the importance of family involvement in TIPS activities. Observational work is needed to better understand the specific requests, actions, and tone of teachers that encouraged the highest levels of effective family engagement in student homework.

Finally, every effort was made to control for differences across homework treatment groups. Specifically, in analyses of standardized test data, the researcher controlled for variation in gender, ability group, ethnicity, free/reduced lunch status, study type, teacher experience, previous test score, and homework group (control, TIPS 1-year, or TIPS 2-year). Accounting for these differences, a significant TIPS effect emerged for family feelings, student attitudes, family involvement in homework, and standardized test scores. Investigations using nested analyses that may simultaneously calculate the individual and classroom effects of the intervention on targeted outcomes may pinpoint more directly some of the possible causes of these TIPS results. Certainly, many questions remain that would benefit from path analyses as well as hierarchical linear modeling.

Practical Suggestions for Teachers

Designing Interactive Homework

Recognize the importance of the interactive nature of the assignment. Teachers should think carefully about how the skill or objective of the assignment may be highlighted in an interaction before writing the actual assignment. Some skills lend themselves to better interactions than others. By identifying the interactive components of the assignment first, one can ensure that the assignment will promote productive and meaningful student-parent interactions.

Do not expect the family partner to teach school skills. The student should compute the answers to problems, write paragraphs, and collect information. The family partner serves as an assistant, never the teacher. All parents, regardless of formal education, should be able to participate in the student-family interaction.

Identify the student and family roles clearly. The directions of the assignment should be clear to students. They should see easily where they will ask for family partner involvement. For example, if the assignment includes important definitions, teachers should write the following statement for students to follow: “Explain the following definitions to your family partner.”

Link skills and objectives to the real world. Try to link the skill and the required student work and interactions to the real world as often as possible. Both students and parents report enjoying such interactions.

Focus on the objective of the assignment. Teachers should be careful not to lose sight of the objective. Because interactive assignments should take about 15–30 minutes of time, it is important for the students’ work to zero in on the assignment’s objective.

Pretest and edit the assignment. Part of the writing process includes pretesting the assignment. Teachers should complete the assignment to make sure that it is doable. If two teachers designed an activity, they should pretest and edit each other’s assignments. Thinking of the average student and parent, consider: How much time is needed to complete the assignment? Are the questions absolutely clear? Are the student and family partner roles clear? Then edit the assignment to improve it.

Vary the types of interactions. Teachers should vary the types of interactions that are required across assignments. Not all activities should ask students to interview a family partner. Students might like to conduct different interactions such as a game, demonstration, or experiment, or collect reactions, memories, or ideas.

Develop assignments you would enjoy completing. Your enthusiasm for the assignments will encourage students to see the value and importance of completing interactive homework. The more excited you are about the activity, the better its reception!

Conclusion

This study reported beneficial results of three longitudinal studies of TIPS interventions compared to regular homework in math, science, and language arts in the elementary and middle grades. Effect sizes and regression models consistently highlight TIPS (especially the 2-year group) as significant and positive predictors of achievement and emotional outcomes over the control condition. Therefore, these findings suggest that teams of teachers can be guided to work together to view homework as a resource that supports classroom teaching. In addition, the efforts of teachers, students, and families to test the TIPS process resulted in an experience and materials that could be used by other teachers of these subjects and grade levels in the same district who conduct similar curricular units for student learning. The longitudinal studies that followed students for 2 years confirmed and extended prior shorter studies to show that when the TIPS interactive homework process is well implemented, student and family emotional and achievement results outweigh the time and costs of the intervention.

Author’s Note

The author would like to acknowledge Joyce L. Epstein for her guidance and support during the course of this research. The author is especially grateful for the partnership of the teachers and district office personnel involved in this study. This work was supported by a grant from NICHD (R01 ADD) to the Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships. The analyses and opinions are the author’s and do not necessarily reflect the policies of the funding agency.

References

Bembenutty, H. (2009). Self-regulation of homework completion. Psychology Journal, 6, 138–153.

Bembenutty, H. (2011). The last word: An interview with Harris Cooper—Research, policies, tips, and current perspectives on homework. Journal of Advanced Academics, 22, 342–351.

Bennett, S., & Kalish, N. (2006). The case against homework: How homework is hurting our children and what we can do about it. New York, NY: Crown.

Cooper, H. (1989). Homework. White Plains, NY: Longman.

Cooper, H. (2007). The battle over homework: Common ground for administrators, teachers, and parents (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Cooper, H., Robinson, J. C., & Patall, E. A. (2006). Does homework improve academic achievement? A synthesis of research, 1987– 2003. Review of Educational Research, 76, 1–62.

Corno, L., & Xu, J. (2004). Homework as the job of childhood. Theory Into Practice, 43, 227–233.

Dauber, S. L., & Epstein, J. L. (1993). Parents’ attitudes and practices of involvement in inner-city elementary and middle schools. In N. Chavkin (Ed.), Families and schools in a pluralistic society (pp. 53–71). Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Eccles, J. S., & Harold, R. D. (1996). Family involvement in children’s and adolescents’ schooling. In A. Booth & J. F. Dunn (Eds.), Family-school links: How do they affect educational outcomes? (pp. 3–35). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Epstein, J. L. (2011). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (2nd ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Epstein, J. L., Sanders, M. G., Sheldon, S., Simon, B. S., Salinas, K. C., Jansorn, N. R., . . . Williams, K. J. (2009). School, family, and community partnerships: Your handbook for action (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Epstein, J. L., & Van Voorhis, F. L. (2001). More than minutes: Teachers’ roles in designing homework. Educational Psychologist, 36, 181–193.

Grolnick, W. S., & Slowiaczek, M. L. (1994). Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling: A multidimensional conceptualization and motivational model. Child Development, 64, 237–252.

Henderson, M. (1996). Helping your student get the most out of homework. Chicago, IL: National Parent Teacher Association and the National Education Association.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Bassler, O. C., & Burow, R. (1995). Parents’ reported involvement in students’ homework: Strategies and practices. The Elementary School Journal, 95, 435–450.

Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Battiato, A. B., Walker, J. M. T., Reed, R. P., DeJong, J. M., & Jones, K. P. (2001). Parental involvement in homework. Educational Psychologist, 36, 195–210.

Kay, P. J., Fitzgerald, M., Paradee, C., & Mellencamp, A. (1994). Making homework work at home: The parents’ perspective. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27, 550–561. 248 Journal of Advanced Academics Family Involvement in Homework Kenney-Benson, G. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2005). The role of mothers’ use of control in children’s perfectionism: Implications for the development of children’s depressive symptoms. Journal of Personality, 73, 23–46.

Kitsantas, A., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2009). College students’ homework and academic achievement: The mediating role of self-regulatory beliefs. Metacognition and Learning, 4, 97–110.

Kohn, A. (2006). The homework myth: Why our kids get too much of a bad thing. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

Kralovec, E., & Buell, J. (2000). The end of homework: How homework disrupts families, overburdens children, and limits learning. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Markow, D., Kim, A., & Liebman, M. (2007). The MetLife survey of the American teacher: The homework experience. New York, NY: Metropolitan Life Insurance Company.

Marzano, R. J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria, VA: Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Marzano, R. J., & Pickering, D. J. (2007). Special topic: The case for and against homework. Educational Leadership, 64, 74–79.

Patall, E. A., Cooper, H., & Robinson, J. C. (2008). Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research, 78, 1039–1104.

Perie, M., & Moran, R. (2005). NAEP 2004 trends in academic progress: Three decades of student performance in reading and mathematics (NCES 2005-464). Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Polloway, E. A., Epstein, M. H., Bursuck, W. D., Madhavi, J., & Cumblad, C. (1994). Homework practices of general education teachers. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 27, 500–509.

Pomerantz, E. M., Moorman, E. A., & Litwack, S. D. (2007). The how, whom, and why of parents’ involvement in children’s academic lives: More is not always better. Review of Educational Research, 77, 373–410.

Sanders, M., Sheldon, S., & Epstein, J. (2005). Improving schools’ partnership programs in the National Network of Partnership Schools. Journal of Educational Research and Policy Studies, 5, 24–47.

Van Voorhis, F. L. (2004). Reflecting on the homework ritual: Assignments and designs. Theory Into Practice, 43, 205–211.

Van Voorhis, F. L. (2008, March). Stressful or successful? An intervention study of family involvement in secondary student science homework. Paper presented at the 14th International Roundtable on School, Family, and Community Partnerships (INEPT), New York City, NY.

Van Voorhis, F. L. (2009). Does family involvement in homework make a difference? Investigating the longitudinal effects of math and language arts interventions. In R. Deslandes (Ed.), International perspectives on student outcomes and homework: Family-school-community partnerships (pp. 141–156). London, England: Taylor and Francis.

Van Voorhis, F. L. (in press). Adding families to the homework equation: A longitudinal study of family involvement and mathematics achievement. Education and Urban Society.

Van Voorhis, F. L., & Epstein, J. L. (2002). TIPS Interactive homework CD for the elementary and middle grades. Baltimore, MD: Center on School, Family, and Community Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University.

Warton, P. M. (2001). The forgotten voices in homework: Views of students. Educational Psychologist, 36, 155–165.

Xu, J. (2009). Homework management reported by secondary school students: A multilevel analysis. In R. Deslandes (Ed.), International perspectives on student outcomes and homework: Family-schoolcommunity partnerships (pp. 110–127). London, England: Taylor and Francis.

Permission Statement

Permission to reprint this article was granted by Prufrock Press, Inc. https://www.prufrock.com.

Comments